二十年前,我知道一位名叫 Arthur Aron 的心理學家, 成功令兩位陌生人愛上了對方。去年暑假,我嘗試將這個實驗應用在自己身上。深夜裡,我獨自站在橋上,看著一個男人的眼睛4分鐘。

我跟他解釋了這個實驗。一男一女通過兩道分開的門進入實驗室。兩個人面對面坐著,問對方一系列私人問題。然後,靜靜地望著對方的眼睛四分鐘。最理想的預期結果,就是這兩個人六個月之後結婚了。

當他繼續陳述另外兩個共同點,我微笑了一下,吞了一大口啤酒。我們亦分享了對上一次哭的故事,並承認了一件事情,我們兩個都相信算命。我們都會跟媽媽分享自己的感情生活。

這些問題令我想到 “溫水煮青蛙”。其實這些問題逐漸地觸碰對方脆弱的心靈。這個實驗之所以能夠成功,是因為通常這些問題的答案可能需要幾個月甚至乎幾年才有可能得知的。

“In particular, several studies investigate the ways we incorporate others into our sense of self. It’s easy to see how the questions encourage what they call “self-expansion.”

又譬如說,“我喜歡你的聲音,我喜歡你的品味、你那些朋友仰慕你的目光。”makes certain positive qualities belonging to one person explicitly valuable to the other.

我喜歡這個研究,不但因為這個研究假設著,愛是一種行動。它還假設影響對方的事情,同時還影響著我。因為我們擁有三個共同特點。因為我們都和自己的媽媽有著緊密的關係。因為,他也讓我看著他。

It’s true you can’t choose who loves you, although I’ve spent years hoping otherwise, and you can’t create romantic feelings based on convenience alone. Science tells us biology matters; our pheromones and hormones do a lot of work behind the scenes.

More than 20 years ago, the psychologist Arthur Aron succeeded in making two strangers fall in love in his laboratory. Last summer, I applied his technique in my own life, which is how I found myself standing on a bridge at midnight, staring into a man’s eyes for exactly four minutes.

Let me explain. Earlier in the evening, that man had said: “I suspect, given a few commonalities, you could fall in love with anyone. If so, how do you choose someone?”

He was a university acquaintance I occasionally ran into at the climbing gym and had thought, “What if?” I had gotten a glimpse into his days on Instagram. But this was the first time we had hung out one-on-one.

“Actually, psychologists have tried making people fall in love,” I said, remembering

Dr. Aron’s study. “It’s fascinating. I’ve always wanted to try it.”

I first read about the study when I was in the midst of a breakup. Each time I thought of leaving, my heart overruled my brain. I felt stuck. So, like a good academic, I turned to science, hoping there was a way to love smarter.

I explained the study to my university acquaintance. A heterosexual man and woman enter the lab through separate doors. They sit face to face and answer a series of increasingly personal questions. Then they stare silently into each other’s eyes for four minutes. The most tantalizing detail: Six months later, two participants were married. They invited the entire lab to the ceremony.

“Let’s try it,” he said.

Let me acknowledge the ways our experiment already fails to line up with the study. First, we were in a bar, not a lab. Second, we weren’t strangers. Not only that, but I see now that one neither suggests nor agrees to try an experiment designed to create romantic love if one isn’t open to this happening.

I Googled Dr. Aron’s questions;

there are 36. We spent the next two hours passing my iPhone across the table, alternately posing each question.

They began innocuously: “Would you like to be famous? In what way?” And “When did you last sing to yourself? To someone else?”

But they quickly became probing.

In response to the prompt, “Name three things you and your partner appear to have in common,” he looked at me and said, “I think we’re both interested in each other.”

I grinned and gulped my beer as he listed two more commonalities I then promptly forgot. We exchanged stories about the last time we each cried, and confessed the one thing we’d like to ask a fortuneteller. We explained our relationships with our mothers.

The questions reminded me of the infamous boiling frog experiment in which the frog doesn’t feel the water getting hotter until it’s too late. With us, because the level of vulnerability increased gradually, I didn’t notice we had entered intimate territory until we were already there, a process that can typically take weeks or months.

I liked learning about myself through my answers, but I liked learning things about him even more. The bar, which was empty when we arrived, had filled up by the time we paused for a bathroom break.

I sat alone at our table, aware of my surroundings for the first time in an hour, and wondered if anyone had been listening to our conversation. If they had, I hadn’t noticed. And I didn’t notice as the crowd thinned and the night got late.

We all have a narrative of ourselves that we offer up to strangers and acquaintances, but Dr. Aron’s questions make it impossible to rely on that narrative. Ours was the kind of accelerated intimacy I remembered from summer camp, staying up all night with a new friend, exchanging the details of our short lives. At 13, away from home for the first time, it felt natural to get to know someone quickly. But rarely does adult life present us with such circumstances.

The moments I found most uncomfortable were not when I had to make confessions about myself, but had to venture opinions about my partner. For example: “Alternate sharing something you consider a positive characteristic of your partner, a total of five items” (Question 22), and “Tell your partner what you like about them; be very honest this time saying things you might not say to someone you’ve just met” (Question 28).

Much of Dr. Aron’s research focuses on creating interpersonal closeness. In particular, several studies investigate the ways we incorporate others into our sense of self. It’s easy to see how the questions encourage what they call “self-expansion.” Saying things like, “I like your voice, your taste in beer, the way all your friends seem to admire you,” makes certain positive qualities belonging to one person explicitly valuable to the other.

It’s astounding, really, to hear what someone admires in you. I don’t know why we don’t go around thoughtfully complimenting one another all the time.

We finished at midnight, taking far longer than the 90 minutes for the original study. Looking around the bar, I felt as if I had just woken up. “That wasn’t so bad,” I said. “Definitely less uncomfortable than the staring into each other’s eyes part would be.”

He hesitated and asked. “Do you think we should do that, too?”

“Here?” I looked around the bar. It seemed too weird, too public.

“We could stand on the bridge,” he said, turning toward the window.

The night was warm and I was wide-awake. We walked to the highest point, then turned to face each other. I fumbled with my phone as I set the timer.

“O.K.,” I said, inhaling sharply.

“O.K.,” he said, smiling.

I’ve skied steep slopes and hung from a rock face by a short length of rope, but staring into someone’s eyes for four silent minutes was one of the more thrilling and terrifying experiences of my life. I spent the first couple of minutes just trying to breathe properly. There was a lot of nervous smiling until, eventually, we settled in.

I know the eyes are the windows to the soul or whatever, but the real crux of the moment was not just that I was really seeing someone, but that I was seeing someone really seeing me. Once I embraced the terror of this realization and gave it time to subside, I arrived somewhere unexpected.

I felt brave, and in a state of wonder. Part of that wonder was at my own vulnerability and part was the weird kind of wonder you get from saying a word over and over until it loses its meaning and becomes what it actually is: an assemblage of sounds.

So it was with the eye, which is not a window to anything but a rather clump of very useful cells. The sentiment associated with the eye fell away and I was struck by its astounding biological reality: the spherical nature of the eyeball, the visible musculature of the iris and the smooth wet glass of the cornea. It was strange and exquisite.

When the timer buzzed, I was surprised — and a little relieved. But I also felt a sense of loss. Already I was beginning to see our evening through the surreal and unreliable lens of retrospect.

Most of us think about love as something that happens to us. We fall. We get crushed.

But what I like about this study is how it assumes that love is an action. It assumes that what matters to my partner matters to me because we have at least three things in common, because we have close relationships with our mothers, and because he let me look at him.

I wondered what would come of our interaction. If nothing else, I thought it would make a good story. But I see now that the story isn’t about us; it’s about what it means to bother to know someone, which is really a story about what it means to be known.

It’s true you can’t choose who loves you, although I’ve spent years hoping otherwise, and you can’t create romantic feelings based on convenience alone. Science tells us biology matters; our pheromones and hormones do a lot of work behind the scenes.

But despite all this, I’ve begun to think love is a more pliable thing than we make it out to be. Arthur Aron’s study taught me that it’s possible — simple, even — to generate trust and intimacy, the feelings love needs to thrive.

You’re probably wondering if he and I fell in love. Well, we did. Although it’s hard to credit the study entirely (it may have happened anyway), the study did give us a way into a relationship that feels deliberate. We spent weeks in the intimate space we created that night, waiting to see what it could become.

Love didn’t happen to us. We’re in love because we each made the choice to be.

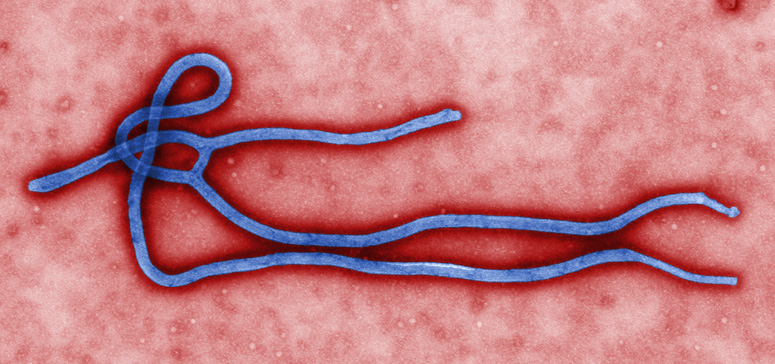

今年爆發的伊波拉病毒疫情,規模為歷年之最。根據

今年爆發的伊波拉病毒疫情,規模為歷年之最。根據 早在1976年就發現了伊波拉病毒,但因為受害者多為非洲居民,生產疫苗或治療藥物無利可圖,所以藥廠遲遲不願投入資金研發。(影像來源:

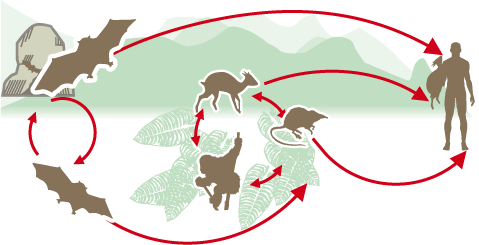

早在1976年就發現了伊波拉病毒,但因為受害者多為非洲居民,生產疫苗或治療藥物無利可圖,所以藥廠遲遲不願投入資金研發。(影像來源: 人畜共生傳染病,佔人類歷史上傳染病的大宗。隨著人類與其他生物間更加密集的接觸,感染的可能性也會增加。(影像來源:

人畜共生傳染病,佔人類歷史上傳染病的大宗。隨著人類與其他生物間更加密集的接觸,感染的可能性也會增加。(影像來源: